Elise Engler |

Wolfgang Ellenrieder |

Emily Carr |

Fernando Botero |

Franz Gertsch |

|||||

Caspar David Friedrich |

Gisèle van Waterschoot |

Jochen Gerz |

John William Godward |

Maurizio Cattelan |

Pawel Nikolajewitsch Filo |

Stephen Conroy |

|||

Georgia O'Keeffe (1887-1986)

"The meaning of a word - to me - is not as exact as the meaning of a color. Colors and shapes make a more definite statement than words. I am often amazed at the spoken and written word telling me what I have painted. I make this effort because no one else can know how my paintings happen.

Where I was born and where and how I have lived is unimportant. It is what I have done with where I have been that should be of interest ." (Georgia O'Keeffe ).

In spite of the fact that Georgia Totto O'Keeffe is widely considered by critics and art historians to be one of the most important American artists of the 20th century, the USPS up to now only issued one stamp featuring one of her well-known flower paintings. The stamp is shown immediately above, top right, and was issued in 1996, ten years after her death. The title of the art work is "Red Poppy".

Georgia O'Keeffe was born on 15th November 1887 in the State of Wisconsin, which joined

the Confederation in 1848. There were seven children in the family, five of which were girls.

Below is shown the US Centennial Wisconsin Statehood stamp, issued 1948:

Instead of displaying colourful stamps I will show a selection of her paintings, hoping that you will like them as much as I do.

Alfred Stieglitz

O'Keeffe had received instruction in drawing and painting as a child in Wisconsin, and by 1915 she had attended classes at the School of The Art Institute of Chicago, the Art Students League in New York, and Teachers College, Columbia University. In that year, however, she consciously rejected aspects of her formal training in order to make personal experience the subject of her art.

Her active career began in the 1910s and continued into the late 1970s, but the paintings for which she is most well known today were completed from the mid-1920s through the 1940s. These works are characterized by subject matter that has become instantly associated with O'Keeffe - flowers, bones, and New Mexico landscapes. In 1916, however, when her work was first exhibited by Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946) - and whom she later married - whose innovations in photography and early support of modern art in America are well known, it was not as obviously dependent on imagery derived from the natural world.

The above work "Red Canna" is a watercolour belonging to the Art Gallery of Yale University. Together with the two works in oil and pastel respectively, all of an almost organic appearance, they display her talents perfectly in different media of totally different nature. The work "Oriental Poppies" (left) belongs to University Art Museum, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

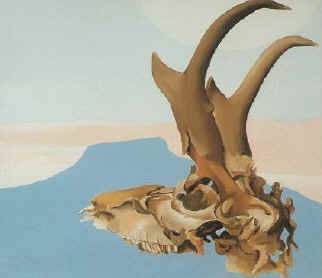

This painting to juxtaposes a form that O'Keeffe came to know well in New Mexico, to where she moved definitively in 1946 after her husband, Alfred Stieglitz' death: An animal skull that she probably found in the desert.

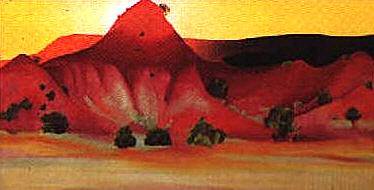

One of O'Keeffe's greatest skills was to paint the light and shade it out in natural forms. She was fascinated by an area of grey black landscape forms in the Navajo country (right) of northwestern New Mexico that she discovered in the 1940s and made it the subject of at least twelve paintings.

Above an FDC issued 1962, commemorating the state of New Mexico's 50th anniversary of statehood

and the brilliant colours found in landscape forms near her Ghost Ranch house in New Mexico inspired many of her paintings of the 1940s. and to the right the brilliant colours found in landscape forms near her Ghost Ranch house in New Mexico inspired many of her paintings of the 1940s.

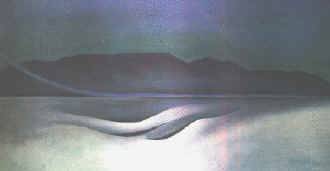

This page can be concluded by nothing else

than paintings from Ms. O'Keeffe's much beloved Lake George (Vermont), whose solitude and wild nature she depicted on numerous paintings throughout her long, active life.

Sources:

Barbara Buhler Lynes (Rizzoli Art Series): Georgia O'Keeffe

Jack Cowart & Juan Hamilton (National Gallery of Art, Washington): Georgia O'Keeffe, Art and Letters

Charles C. Eldridge (Smithsonian Institution): Georgia O'Keeffe

Georgia O´Keeffe, Photos Alfred Stieglitz

With great fanfare, the Metropolitan Museum of Art last summer mounted " Georgia O'Keeffe: A Portrait by Alfred Stieglitz ," a suite of 81 photographs of the great American painter made between 1917 and 1937 by the man who was first her sponsor, then her lover, and eventually her husband. All told, the full series comprises more than 300 images, and has never been publicly presented in its entirety (whatever Stieglitz might eventually have determined that to be).

For years after its conclusion, this completed but not definitively edited project appeared only in bits and pieces. In 1978, thanks to a loan from O'Keeffe, the Met showed 51 of them. Now that institution has acquired that original group, plus an additional 30 prints. Celebrating that accession, this exhibit, if it does not lay out before us the complete opus, at least displays its framework and many of its central components.

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O'Keeffe, 1918

Courtesy of the Metropolitian Museum of Art

Yet it does so in ways I find extremely problematic. The difficulties begin with the presentation itself. Recent researches in the preservation of photographs have taught conservators and curators the perils of subjecting photographs to extended periods of illumination. And these are particularly rare, precious and valuable works of their kind. So, to protect the images from deterioration, the level of light in the Met's photography galleries has been subdued - so much so that, in many cases, one cannot actually read the images, especially the generally low-key platinum and palladium prints (The less numerous silver-gelatin prints fare somewhat better). This raises the vexing question of whether there is work for which prolonged public exhibition is simply counterproductive and inappropriate.

Furthermore, for safety's sake, the prints of course have been framed under glass, which catches the moving reflections of the viewer and everyone else within range. So, even were the galleries empty of all save oneself, these would be the worst possible physical conditions under which to examine such work, which is meant to be looked at in good light and at length, even held and turned in the hand, so that one can see and respond to Stieglitz's delicate handling of light-sensitive metals in his rendering of flesh and other substances, and appreciate the difference between these various forms of photographic print. My readers know that I usually advocate an eyes-on relationship to any work of art, but in this case I feel no compunction in proposing that you'll do just as well - perhaps even better - by skipping the show and applying your entrance fee instead to the fine accompanying monograph (MMA/Abrams, $60 hardbound), from

Beyond that, curator Maria Morris Hambourg has made the curious decision not to organize the prints chronologically, but rather (in the rooms devoted to the 1978 group) to follow O'Keeffe's eccentric sequencing, and in the room containing the additional images to arrange them according to some plan that remains unarticulated and obscure. This means that one does not get to see the collaboration between model and artist - and this is very much a collaborative project - nor to see O'Keeffe mature and age, or Stieglitz's vision evolve. It also means that one never gets to see variants of the same pose, or images clearly made during the same session, side by side. This obviates, for no good or apparent reason, any glimpse into Stieglitz's working method as a picture maker.

Viewing conditions aside, there are additional reasons to pass on the show. I happened to go on a Thursday afternoon that proved unexpectedly crowded. Perhaps this was due to the Garth Brooks extravaganza planned for that evening just west in Central Park, though I find it hard to imagine any audience overlap. I'd venture that the attendance resulted more from summer tourism and the hype to which this exhibition - like all such shows nowadays - has been subjected. And the no-bones-about-it purpose of that hype is merchandising.

The Met is now full of shops; indeed, both coming to and going from this exhibit by two different routes, I could hardly keep from bumping into another one, giving me the odd impression of strolling through someplace like Brooks Brothers in the 1950s. The Japanese, I read, have pioneered in putting presentational venues for art into department stores; taking a cue from this, perhaps, today's museums seem increasingly intent on intruding the option of shopping into spaces formerly restricted to the formal display of works of art. Indeed, right outside the photography galleries, and clearly visible when one was inside them, stood a shop aswarm with Stieglitz/O'Keeffe tzotzkes: books, posters, notecards, even some dubious artifacts - apparently mere loose reproductions from the monograph - matted, framed, identified disingenuously as "framed prints" and priced at $65 (frame included).

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O'Keeffe, 1921

Courtesy of the Metropolitian Museum of Art

Stieglitz and O'Keeffe would have loathed everything about this presentation of their project: the inadequate lighting, the gossipy hucksterism centered around their private lives, the distracting traffic in trade goods. These factors created an entirely inappropriate context within which to see such work as this: quiet, patient, nuanced, slow-paced, intimate, determinedly non-commercial. Its two protagonists were after something else - something about themselves, something about each other, something about photography - and more often than not they achieved it, though little of it survives the onslaught of the surround that the Met constructed for this exhibition.

Yet I must also ask this: even under ideal circumstances, could we - can we - today possibly get back to what these pictures meant, individually and cumulatively, in their own time? I don't mean what they meant in the Stieglitz-O'Keefe relationship, which will forever remain a mix of enigma, myth, psychobiography, speculation and gossip, but what they meant as collaborative works of art intended for eventual public display. For these were not mere souvenirs or family-album snapshots; almost all are posed (the earliest required four-minute exposures), formally organized, and printed to exhibition-quality standards by a virtuoso in that craft.

Whatever private impulses led to the initiation of this sequence, Stieglitz (with O'Keeffe's full consent) made many of them public early on: 45 were shown in a 1921 retrospective of his work, generating considerable controversy in the process, and he exhibited an additional 30 two years later. Stieglitz continued to show and publish segments of the sequence until his death in 1946, after which O'Keeffe continued that activity.

So, from almost the beginning, they meant this work to be seen and considered in the context of the field of ideas - in photography, in the other arts, and even in literature - of its time. Yet it appears to have grown organically, out of itself and their complex relationship, rather than according to any initial or subsequent plan - an unusually fluid, aleatory method for a photographic project of that period.

On the most obvious levels, it reads as biography/autobiography, tracing O'Keeffe's maturation and the growth of their deep yet shifting involvement with each other. No previous photographic project had essayed anything similar, so it is unprecedented and pioneering on that score alone. Yet what it says in those regards is no less important or unconventional. In these images O'Keeffe goes from appearing traditionally feminine and reserved to becoming a woman willing to pose frontally nude for publicly shown images in which she was identifiable, and from looking shy, fragile and girlish to looking tough, no-nonsense, and often decidedly mannish. Indeed, though much has been made of the expressiveness of her hands, often a central element in these images, it seems to me she had a repertoire of perhaps four mannered hand gestures, while her face proves infinitely expressive, varied and mobile.

Just as it leads us through the flowering of an unexpected individual character, so the series speaks of an unanticipatedly intricate relationship. In some ways it almost exactly reverses the outward form of their involvement. The early images resonate with passion and a sense of conscious disclosure of private concerns. Oddly, almost as soon as they married they began on many levels to draw apart. As their lives progressed towards a more distanced, less physically involved companionship, so the work moves toward a manifestation of a man and a woman engaging with each other less as lovers than as equals; what is lost in terms of eroticized intimacy is supplanted by calm acceptance, deep friendship, long-term commitment and clear-sighted recognition. They are the photographs of a man who learned to let go of the woman he loved most in order to see her whole.

Before Stieglitz, no exhibiting photographer had ever spent so much time looking at one single person. The building up of a portrait in this mosaic fashion - a collection of hundreds of studies of different aspects of the same individual, made in different places over an extended period of time - had no precedent in any medium, and was something which, if not necessarily photographic, peculiarly suited the medium. Stieglitz knew he was innovating; he titled that first 1921 exhibition of these works "Demonstration of Portraiture," and the possibilities he opened up thereby have resonated down the corridors of photography ever since. One can find their echoes in the work of Harry Callahan, Robert Frank, Sally Mann, Nicholas Nixon, Emmet Gowin, Nan Goldin and countless others who, consciously or not, have taken that idea elsewhere - though none, I think, has ever taken it further.

Finally, I think that something must be said about this work's relationship to the most radical art of its time - art which, it should be remembered, Stieglitz himself studied and championed and exhibited and published and discussed first-hand with many of its makers. Much has been made of Paul Strand's photographic response to Cubism, visible in the early work of Strand's that Stieglitz showed at his "291" Gallery and published in the final issues of the journal Camera Work from 1916-17 - that is, at exactly the time Stieglitz became involved with O'Keeffe and commenced the "Portrait."

Strand often receives credit for introducing Cubist ideas to photography. Yet I'd propose that Strand absorbed and reflected in his work primarily the look of Cubism, not its theoretical underpinnings. Stieglitz didn't learn of Cubism from Strand; he'd published Picasso, and Gertrude Stein on Picasso, before Strand became his protege¥. Though they become increasingly modernist in style, even the later images in the "Portrait" don't appear particularly Cubist. Yet I'd argue that the very premise of the project, once Stieglitz undertook it as such, was inherently Cubist: the apprehension of a subject by studying it from a variety of vantage points, and the montaging of those diverse observations into a single final work. Notably, he always referred to this project in the singular, calling it "A Portrait" rather than "Portraits," which suggests that he saw it as one multi-faceted statement rather than many separate ones. For this viewer, at least, here is where Cubism in photography begins.

Unless we were present and conscious of it at its birth, we can never truly feel what a work meant in its own day to its contemporaries. We can only try to imagine ourselves back to the moment of its conception and debut, when the first attempts to make meaning of it took place. Few today were even born when this astonishing nexus of ideas hit the ground running, and none can remember that occasion. What it innovated we now take for granted, as received. It's worth your time to spend a slow day in a chair with this book, thinking about what its contents represented in the world of your grandparents and great-grandparents, back when it functioned as a working definition in photography of what Robert Hughes calls "the shock of the new."